Money Market Funds, Large CDs, Small CDs All Surged: Americans Figured it Out

[ad_1]

Banks, forced by competition from money market funds, got the memo.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

Money market funds have been paying over 5% since about April 2023, up from near 0% in April 2022, and Americans are liking it. A lot. And that has forced banks to compete for deposits by offering attractive interest rates on CDs. And Americans have flocked to those too.

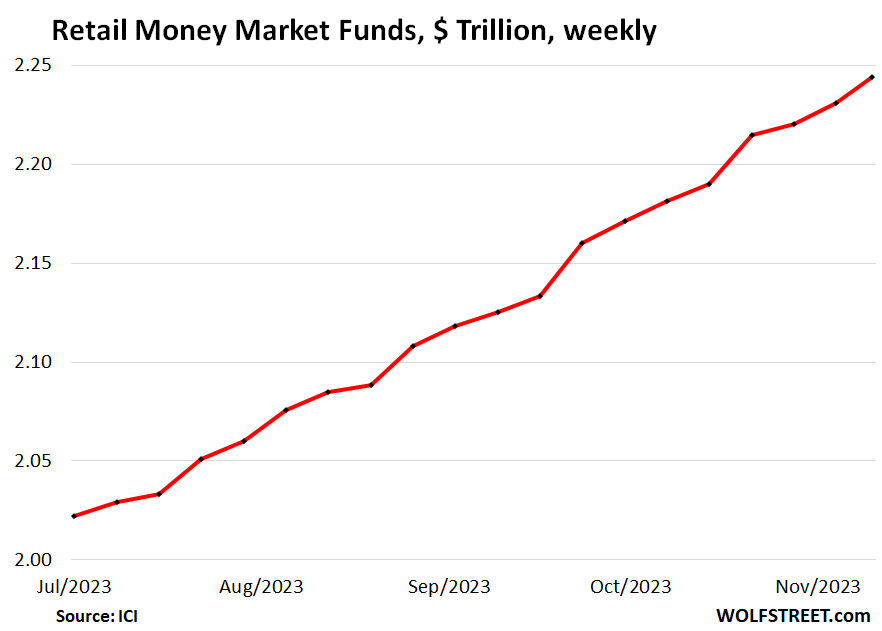

Money market funds for retail investors rose by 0.6% in the latest reporting week from the prior week, by 2.5% over the past four weeks, and by 8.9% over the past three months, to $2.24 trillion, ICI (Investment Company Institute) reported on November 22. This includes funds that invest in government instruments, such as T-bills; funds that invest in tax-exempt securities; and prime funds that invest in non-Treasury assets.

Those are just funds sold to retail investors. Money market funds (MMFs) are divided into two major categories in terms of who they’re targeted for, based on the language in their prospectus; and we look at them separately:

- Funds sold directly to retail investors (chart above)

- Funds sold to institutions such as an employer, trustee, or fiduciary on behalf of its clients, employees, or owners (chart below)

MMFs are mutual funds that invest in relatively safe, short-term securities, such as Treasury bills, repos, including what the Fed offers and calls “Overnight Reverse Repos” (ON RRPs), high-grade commercial paper, and high-grade asset-backed commercial paper.

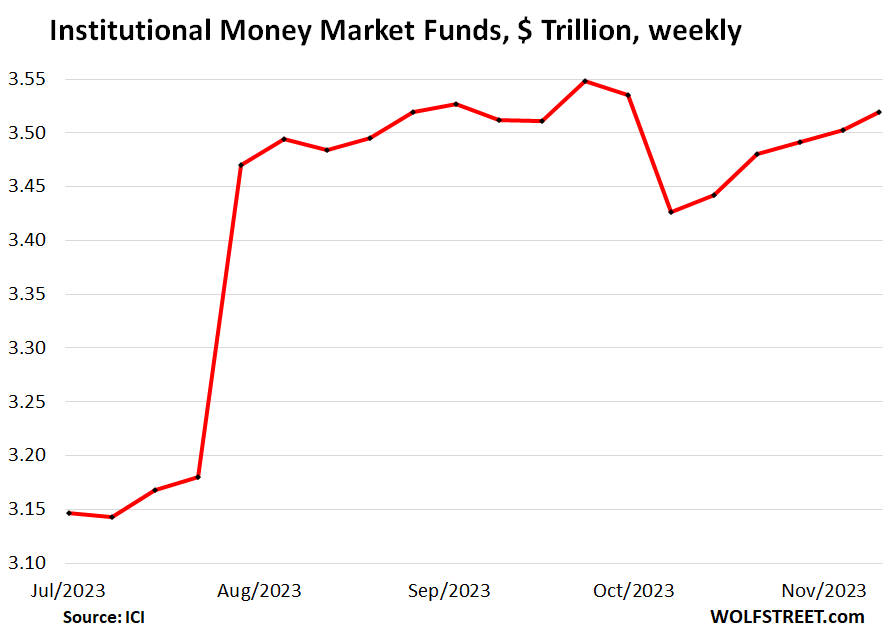

MMFs for institutions rose by 0.5% last week, by 2.2% over the past four weeks, but only by 1.4% over the past three months, after the dip in October, to $3.52 trillion.

Individuals are indirectly among the holders of these funds since the institutions include employers, trustees, or fiduciaries who buy those funds on behalf of their clients, employees, or owners.

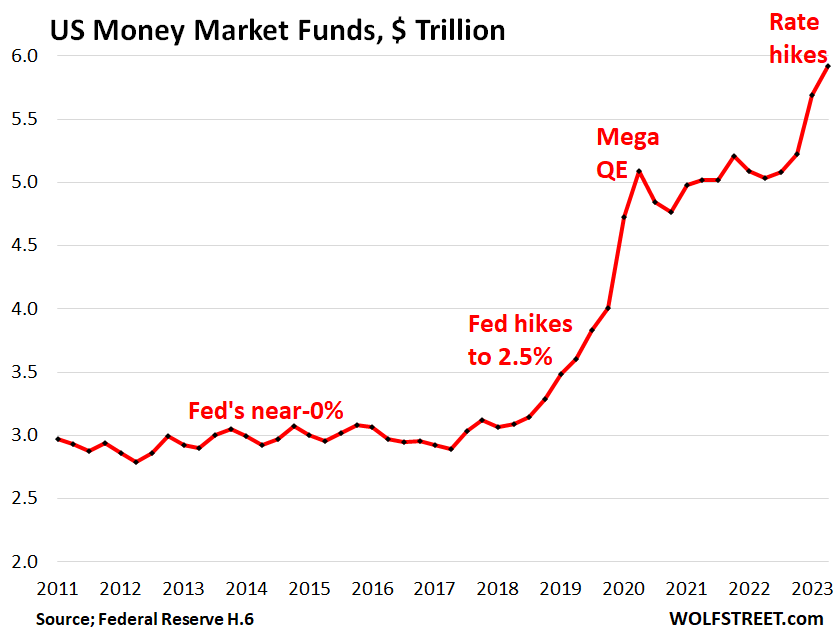

Total MMF balances rose by 2.3% over the past four weeks and by 4.2% over the past three months, to $5.76 trillion.

The ICI makes only the past 20 weeks of data available and excludes ETFs and funds that invest primarily in other mutual funds.

The Federal Reserve releases a slightly different metric on a quarterly basis as part of its money stock series, currently through Q2, and it has been the same song. You can see how the balances swell when the Fed hikes rates, first in the 2017-2019 period, and then again big time this year (data only through Q2).

Money-printing and money market funds. But note in the chart above how the mega-money-printing binge that started in March 2020 created so much liquidity that it went also into money market funds, even when they returned near 0%, which triggered its own set of problems as these funds had to buy T-bills, and their demand for T-bills pushed down the T-bill yield to 0% and even below 0%.

This cause all kinds of fears that some of the MMFs could “break the buck” because their 0% income or even negative income didn’t cover the fees and expenses and could cause the NAV of the fund to drop below $1, which could trigger a run on the fund, which would then trigger forced selling by those funds, panic, contagion, and the whole schmear.

Which is why the Fed offered overnight repurchase agreements (ON RRPs) to the MMFs. The ON RRPs did pay interest, and the Fed lifted that RRP interest rate with each rate hike. We have discussed RRPs and their now plunging balances here.

Banks now have to compete with MMFs.

Deposits are loans from bank customers to the banks and form the backbone of bank funding. When those deposits flee, as depositors yank their money out because they don’t like what they see or the interest they get, banks can collapse, as we have seen in ample detail with Silvergate Capital, Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and First Republic.

And so banks have gotten the memo, and they’re offering CDs that yield 5% and more, and savers have flocked to them. CDs, which have a maturity date, provide funding that is more stable than savings or checking accounts whose cash can be yanked out instantly via electronic funds transfer.

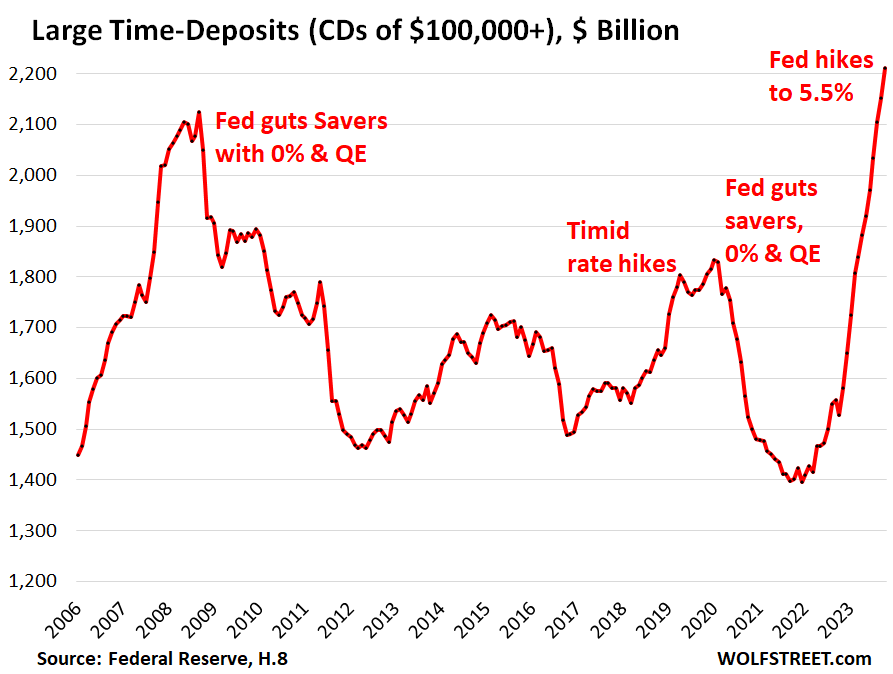

Large Time-Deposits – CDs of $100,000 or more – surged by 60% since the Fed began its rate hikes, to $2.1 trillion at the end of October, from about $1.4 trillion in March 2022, according to Federal Reserve data.

The Fed’s interest rate repression during the Financial Crisis – which sacrificed the cashflow of yield investors, such as savers, at the altar of asset-price inflation – caused banks to cut the interest rates they were paying on CDs to near-0%, and CD balances plunged, as deposits mostly reverted to other types of bank accounts that paid nothing and whose balances continue to swell.

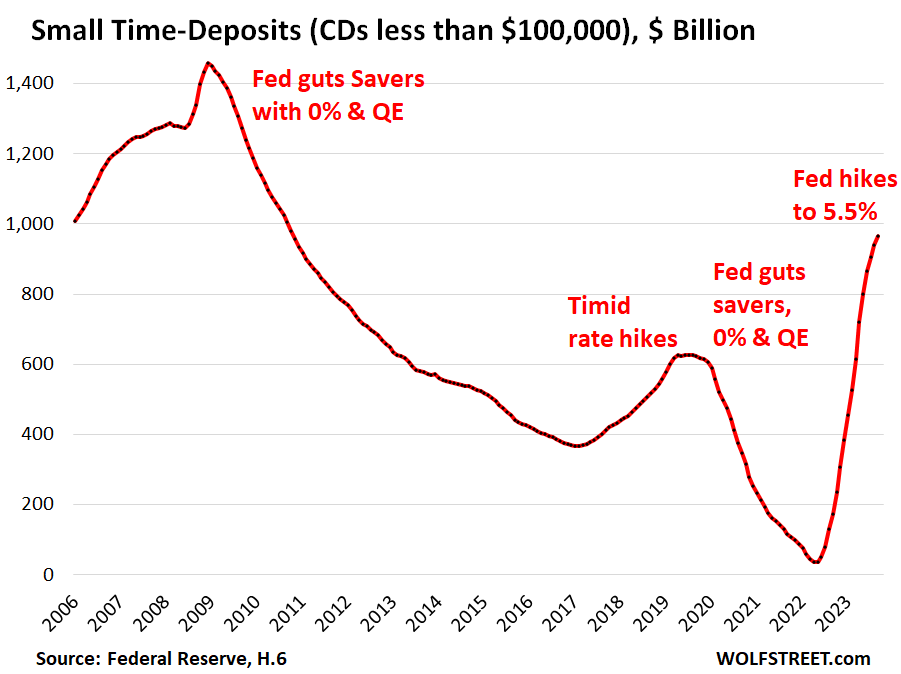

You can see the rhythm. The timid rate hikes from December 2015 through December 2018 caused these time deposits to rise. The Fed’s interest rate repression from March 2020 caused CD balances to plunge. Since the rate hikes began in March 2022, CDs have become attractive again, and investors flocked to them:

Banks offered “brokered CDs” via brokers to investors with brokerage accounts that weren’t necessarily the banks’ customers in order to attract new deposits as their existing deposits began to flee the 0.1% rates that the banks were still paying. And then very reluctantly they stopped trying to endlessly screw their existing customers and began to offer 5%+ CDs to their existing customers to retain the deposits they still had.

Small Time-Deposits – CDs over less than $100,000 – surged from just $36 billion in May 2022 to nearly $1 trillion by the end of September, the latest data available from the Fed’s H.6 money stock measures. It is likely that they continued to surge in October.

These small CDs reflect what regular folks are doing with their savings, and they too are now finally earning some income on their investments – which is encouraging people to save a little more:

CDs are not the only bank savings products that have become attractive by the force of competition with money market funds. Banks are also offering higher interest rates on savings accounts, some going to 5% and beyond, but the bank can change those rates without prior notice, and customers can yank their funds out, unlike CDs whose rates and funds are locked in until the maturity date.

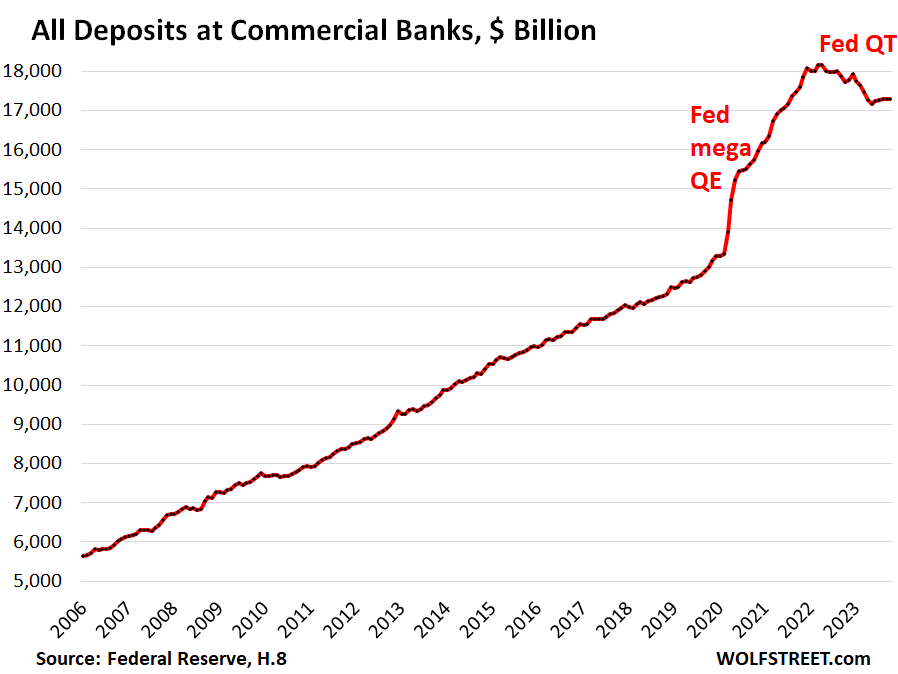

All deposits by all commercial banks – CDs, savings accounts, checking accounts, transaction accounts such as corporate payroll accounts, etc. – have dropped by $890 billion since the peak in March 2022, to $17.3 trillion, after the mega-money-printing binge starting in March 2020 had cause them to spike.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()

[ad_2]

Read More:Money Market Funds, Large CDs, Small CDs All Surged: Americans Figured it Out

Comments are closed.