“Bodies Bodies Bodies” director: “When the Wi-Fi goes out, the demons come in”

[ad_1]

Director Halina Reijn’s “Bodies Bodies Bodies” is a challenging and intelligent film that is much more than the sum of its parts.

On the surface “Bodies Bodies Bodies” is simple: it is a slasher whodunit comedy horror ensemble where a group of obnoxious rich young people (with notable performances by “Borat 2” star Maria Bakalova and Lee Pace) are stuck in a mansion that is stocked with illegal drugs and alcohol during a hurricane and then deprived of access to the internet and functioning phones. Someone dies under suspicious circumstances . . . and then mayhem ensues.

“Bodies Bodies Bodies” could have easily been a play: it is set in one location and explores timeless themes such as human nature, trust, fear, and the all too intoxicating allure of violence and paranoia.

But Reijn and her ensemble have created something much more where “Bodies Bodies Bodies” becomes an indictment of a culture of narcissism, loneliness, and social atomization where the internet, social media, and phones have negatively impacted too many people’s ability to have meaningful relationships with one another and by doing so encouraged the worst aspects of human behavior.

At its best, the horror film genre offers a powerful moral critique of society by exploring the darkest parts of the collective (sub)conscious and other behavior. “Bodies Bodies Bodies” is firmly within that tradition as Reijn skillfully manipulates the audience and their expectations before they hopefully arrive at some moment of introspection about their own complicity with the horrible human behavior they have witnessed on the screen.

In this conversation with Salon, Reijn addresses crafting an entertaining genre film while exploring deeper questions, being vulnerable through art and trying to get people to look up from their smart phones.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How are you feeling right now? What’s the journey been like to get to this point?

I feel grateful. It is very exciting to be able to make a film on a bigger stage than the country where I live in, Holland, which is a very small country. I’m grateful and I’m nervous and happy all at the same time.

What was it like to watch the movie with an audience?

That happens often during the editing process. You also watch the film in the theater with the producers, representatives from the studio, and other people you personally invite. It is of course way more exciting to watch your finished film with a real audience. For me the big moment was watching the movie at South by Southwest, because at that point, we had only shared it with insiders. I have never been more nervous and that includes my time on stage.

They reacted so warmly and enthusiastically. The audience was talking to the screen, laughing and screaming. I had never witnessed that before.

When did you realize you had something cohesive and the film felt real?

“When the Wi-Fi goes out, the demons come in, and we don’t know how to deal with a crisis.”

There was a moment while we were editing the film, and I realized we had something good. We showed it to A24, and they felt the same way.

We shared it at a certain moment in the process with A24, and the response was really good. “Bodies Bodies Bodies” is a genre film. When the audience really approves of it and can follow the beats of the film like they did at South by Southwest then you know the film is resonating.

Films like other works of art are in dialogue with the public and the larger world. What is “Bodies Bodies Bodies” saying to the audience?

“Please, put your phone away. Look at person in front of you – look them in the eyes.” That is what the film is saying. The film is also saying, “It’s OK, don’t worry. We’re all dark and light. We are a mix of demons and innocent little children. Guess what? That is OK.” If we deny that reality and try to pretend that we are just binaries of good and bad, then that is not true. That is not human growth. That’s a very dangerous way of thinking and we need to own the fact that we are shadow and light.

Maria Bakalova and Amandla Stenberg in “Bodies Bodies Bodies” (A24 / Gwen Capistran)Loneliness and social atomization are a type of epidemic and public health emergency across the West right now. There is a real crisis of human intimacy and civility that is in large part being caused by digital technology, social media, the Internet and the like.

Maria Bakalova and Amandla Stenberg in “Bodies Bodies Bodies” (A24 / Gwen Capistran)Loneliness and social atomization are a type of epidemic and public health emergency across the West right now. There is a real crisis of human intimacy and civility that is in large part being caused by digital technology, social media, the Internet and the like.

I don’t want to sound too old, but my father used to teach me how I can make a fire from more less nothing so that I could survive in the forest or out in the wild somewhere. Now you have death by GPS because people are living by their phones and when they don’t have the Internet they are in big trouble.

“The ritual of the slasher and the ritual of the murder mystery is a construct. And within that construct, I want to be contemporary and make an intervention about this moment.”

My movie is delivering that message. When the Wi-Fi goes out, the demons come in, and we don’t know how to deal with a crisis. We don’t actually look at what’s going on. We’re just focused on this alternate world that is in a smart phone and seems to be connected to our bodies.

There is a great danger in that. It is our obligation as filmmakers and creative people who are telling a story to address that danger, even if in a humorous way.

“Bodies Bodies Bodies” has a remarkably simple premise. People versus nature, people versus each other, people versus themselves. It could easily have been a play. How did you manage the process of adapting the film from the source material and the other creative decisions that involved?

When I got the first draft of the script, it was something completely different. There was still a killer. The game is what intrigued me.

I want to make a film about human nature. The ritual of the slasher and the ritual of the murder mystery is a construct. And within that construct, I want to be contemporary and make an intervention about this moment, the times in which we are living through together. “Bodies Bodies Bodies” has a very simple setup. In that way it is like a play. One house, one location. There’s a hurricane, so it’s the characters against nature. But at the same time, it’s mainly them against themselves because the Wi-Fi being gone is much worse than the hurricane for them. It’s even worse than the violence. The Wi-Fi not working is the horror for these characters and the types of people they represent.

The film could have easily been a lazy superficial diatribe about “those kids today!” and how we, the previous generations, are so much smarter and wiser and responsible than they are. How did you avoid that pitfall?

Being very aware of that trap is the first step. The movie is focused on this younger social media Instagram generation, so we wanted to make it very authentic by making sure the actors in the film were collaborators in the creative process. That is something I learned from the theater. I grew up in communes so we’re all contributing. “So I need you guys to tell me, is this how you speak? Is this the music you would listen to? Is this a joke you find funny? Would you want to use another word?”

I really challenge them to be my collaborators instead of just executioners of whatever I thought out in my bed as a 46-year-old.

Is technology going to take us over, or are we in charge? That is a timeless dilemma.

“Bodies Bodies Bodies” is also a very old story about humans being locked up in one space and how they are going to respond to a crisis.

And then in the end it turns out that everything that happened in the movie was just an almost irrational reaction. There’s no monster under the bed. There’s no ghost. There’s no serial killer.

The worst enemy is yourself, and the killer is within you.

Pete Davidson in “Bodies Bodies Bodies” (A24 / Gwen Capistran)“Bodies Bodies Bodies” is very much a movie of the present with its critique of this cultural moment and technology. But those questions about human behavior and technology are actually very old. You could easily make a few changes to the story, and it would still work in another era.

Pete Davidson in “Bodies Bodies Bodies” (A24 / Gwen Capistran)“Bodies Bodies Bodies” is very much a movie of the present with its critique of this cultural moment and technology. But those questions about human behavior and technology are actually very old. You could easily make a few changes to the story, and it would still work in another era.

“In all of us there is a beast. In all of us there is a killer.”

I did a play for 15 years called “The Human Voice” by Jean Cocteau. It’s a monologue, a woman on the telephone with her lover. And in the end, she uses the telephone cord to hang herself. He wrote this right after the telephone was invented, and the whole thing is about how technology is in between humans and why don’t they just sit down and look at each other. If they talked face to face, then the woman might not have [died by] suicide. Those themes resonate today even though the technology is different.

There’s not a lot of exposition in the film. But as a slasher film whodunit you have to break the fourth wall to lead the audience along to what they are expecting to be a twist or surprise at the end because they understand the genre tropes. How did you figure out that balance?

I put myself in the position of the audience. That is something that I learned from performing on stage. You are completely conditioned to be focused on what is in the mind of the audience. I wasn’t sure if I could be successful with this film because it was my first genre piece, but I somehow felt really at home in it.

I also didn’t want to explain too much to the audience. I wanted to challenge them to make up their own story and fill in the blanks and not be spoonfed with, “This is the innocent person, and this is the person and this is going to happen now.” I want to make them feel safe within the ritual of the slasher film. They know, “OK, a lot of people are going to die. They’re all going to be in one house. There’s this hurricane.”

But the rest, I do want to keep the audience at the edge of their seat and guessing and just hoping they’ll be surprised and there’s enough twists and turns. I also want to bring a type of meta perspective and awareness to the logic of the horror film and slasher tropes.

What is the moral judgment at work in the film? What is the teaching?

In all of us there is a beast. In all of us there is a killer. There is also an innocent person inside all of us. We are all layered. We cannot deny the shadow side within us. My films are not going to provide an easy moral answer that everyone will like because my goal is not to leave the viewer feeling safe and comfortable. In the end, what does it take for us to become an animal?

What is a “normal life” like for this Instagram, Twitter, social media generation? The film is deeply critical about these questions.

This is a very challenging time to be a young person. I’m very happy, also, as a girl that I didn’t grow up with a smart phone in my hand. Everybody grows up in front of a camera now. There’s so much pressure on them. What is normal? I don’t know, but I hope to find humanity within that wide ranging experience.

Social psychologists and others have documented how these new technologies and other social forces are creating a deep sense of disconnect and awkwardness about substantive human intimacy and meaningful relationships among this generation.

I feel myself also being part of this now and more scared of intimacy than ever before. I just feel it’s something we need to address, without saying, “Oh, we should go back to the old days.” I don’t want to say that, but we do need to be aware of what’s happening, and we do need to address it in our works of art and media and public conversations more generally.

Rachel Sennott and Lee Pace in “Bodies Bodies Bodies” (A24 / Gwen Capistran)As an outsider, what do you see about this country that native-born Americans may not?

Rachel Sennott and Lee Pace in “Bodies Bodies Bodies” (A24 / Gwen Capistran)As an outsider, what do you see about this country that native-born Americans may not?

I had a very elite education in a theater school. In Holland, that is totally free. The other day I mentioned to a friend who is American that I had a therapy appointment. And she’s like, “Oh, how much does it cost?” I had to pause for a second. It is free in my country. She couldn’t believe it. As a European I take healthcare as a given.

Here in the U.S., I’m constantly aware of the fact that I could be forced to live in my car next week. That is how it feels to me. I see so much homelessness. I see so much pain. I see so much poverty. I also see people being who are extremely rich and have more money than I have ever seen in my life.

There are some obvious influences at work in “Bodies Bodies Bodies.” There is “The Twilight Zone” and Hitchcock. Agatha Christie. John Cassavetes. I also kept thinking about “Kids” while I rewatched the film. Who else are you in dialogue with?

There are the classic plays of course. “Kids” is a huge inspiration too. The opening of “Bodies Bodies Bodies” is actually an homage to “Kids.” Paul Verhoeven is also a great influence on my work.

I have a great appreciation for Verhoeven. He and Cronenberg are two of my favorite directors. What about Verhoeven speaks to you?

I love his film, “The Fourth Man.” I love his film “Elle” a lot. I think it’s amazing. I really like all his films. Having done “Black Book” with him, I fell in love with how he works, his passion, his energy. I even love “Showgirls.” I’m very much in awe of Verhoeven. He’s still so conscious of his times and creative and busy, and I hope I will end up like him when I’m his age.

What is your creative voice?

What does it take for me to become an animal? I also preface honesty. To avoid the vanity and ego. That is something I try to do in my art and personal life. I’m also asking that of my actors. Acting is reacting. So that is what I’m looking for at all times, honesty in my DP, how he handles the camera. It’s got to be raw. It’s got to be brutally honest. That is my main style. To be truthful.

How much do you share, as an actor, as a human being, with others? How much do you keep for yourself? Because we know that many creative people are ultimately destroyed by being too vulnerable and honest with the world. How do you find that balance?

I didn’t keep anything for myself. I think that’s also why I retired acting. I quit acting because I wasn’t able to keep that balance at all.

I appreciate that question a lot because I feel that is the hardest thing to do. It was also my style on stage, it is too much. So you have to become more of a technical actress at a certain point because otherwise you just give away too much. I feel much more comfortable being in the director’s chair. I can still give everything, but it doesn’t feel so radical because it’s no longer about my body or my voice. It’s just more of an intellectual gift that you give, and you can take care of everybody on the set. It means you can take care of your actors and let everybody grow and blossom. I enjoy being part of that.

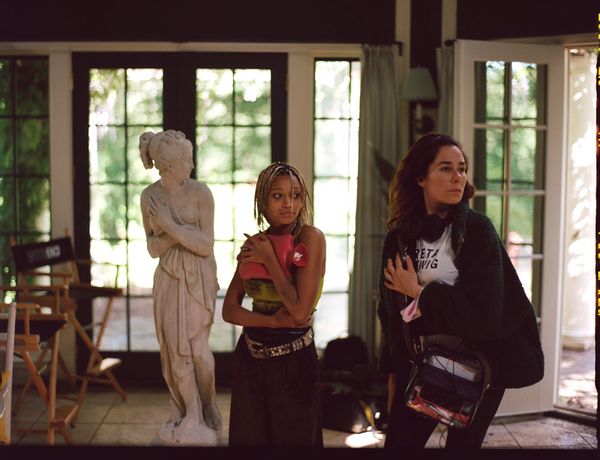

Amandla Stenberg and Halina Reijn in “Bodies Bodies Bodies” (A24 / Erik Chakeen)One of the main themes of “Bodies Bodies Bodies” is generational, cultural, as well as individual malignant narcissism. What happens to the narcissist when they are deprived of their narcissist fuel, that attention?

Amandla Stenberg and Halina Reijn in “Bodies Bodies Bodies” (A24 / Erik Chakeen)One of the main themes of “Bodies Bodies Bodies” is generational, cultural, as well as individual malignant narcissism. What happens to the narcissist when they are deprived of their narcissist fuel, that attention?

If they don’t get the attention, then they become very insecure. But the other side of narcissism is fear. We live with the camera now everywhere. It encourages the narcissism. “Do you like me? Do you love me?” That narcissism is very unhealthy. The constant mirror is too much.

How do you want people to feel when they leave the film?

I hope that they feel the darkness but that they also laughed and had a good time. I also hope that the viewers talk about the movie and that it provoked some insightful conversations. “Bodies Bodies Bodies” is about loneliness and how we need to feel connected to each other in healthy ways. I really hope that people will feel more connected with one another after the conversations they have about the film.

Read more

about this topic

[ad_2]

Read More:“Bodies Bodies Bodies” director: “When the Wi-Fi goes out, the demons come in”

Comments are closed.